(Dedicated to Stan Lee, now in Valhalla)Â

I still cringe! Whenever, that is, I think how many people have told me over the years that their mom took the opportunity while they were off at college to throw away their comic book collections!  I flinch even more, however, when I hear moms still today snapping at their kids, “What are you reading that cheap trash for?†Money figures into it, because if those earlier moms hadn’t trashed their kids’ collections, they’d likely be worth a pile of money now. And because today’s comics cost so much more (often three or four bucks!), it’s not even “cheap†trash anymore! And that makes the case I want to argue here even harder to make, because I want to convince you that, while comic books are no longer cheap, they sure aren’t trash either. Instead, I believe they may form a crucial portion of your child’s education.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Fan

I admit to being a full 64 years old, but my interest in comic books and superheroes is hardly some sort of mid(?)-life crisis behavior. I started reading the four-color epics when I was, what? About 5 or 6 years old, I guess, when they cost a mere dime! A cheap ticket into an alternate universe that turned out to have a lot more to do with this one than I realized then. For some reason, back then I always pictured Superman as being about 40 years old. Superman, Batman, Captain America and the others were authority figures for me. They were survivors of the so-called Golden Age of comics, published through the forties and fifties, members, so to speak, of Tom Brokaw’s “Greatest Generation.†But when Stan Lee’s Spider-Man came along, I related to him in a whole new way. Like me and many other young nerds, this superhero was a teenager, and his paranormal abilities did not make their problems vanish. Knowing himself superior to thick-headed bullies like Flash Thompson, Peter Parker nevertheless had little opportunity to vindicate himself against the jockish taunting. All the jocks knew was that Peter was a chemistry major who kept to himself. He was absorbed not only by how to beat the latest tactics of the Vulture and the Green Goblin, but also whether his part-time job could enable him to pay for his aunt’s medicine. This was a unique sort of character at the time, though a legion more soon copied him. And the unique experience for the young reader was that, if Spider-Man’s mundane problems didn’t vanish during the course of the comic book, neither did the reader’s! The hint was clear that even the great overcome despite their drawbacks, and these drawbacks are not always melodramatic. I never had to square off against Dr. Octopus, but I did have to struggle with the ridicule of insensitive jocks. Spider-Man told me the truth about me.

So I found solace in the garishly colored pages. But that’s not all. I found many other treasures that your children will surely find as well. For one thing (and this alone is worth a lot more even than comics cost today): I became interested in reading. I guess you could get something out of a comic book just looking at the nice pictures, but I’ve never known anyone who was satisfied with that. I read innumerable comics, actually read them, and they became a direct path into reading real books. Specifically, around 1966 (the Turtles’ Happy Together was just out on the radio), I was struck by a story (Archie Goodwin wrote it, Steve Ditko, Spider-Man’s artist, drew it) in Creepy that fell into a fantasy genre new to me, Sword and Sorcery. Not long afterward, I chanced to spot a paperback book on the rack in the stationery store where I bought my comics. It was the Lancer Books edition of Conan the Warrior by Robert E. Howard. Little did I know that he was the very creator of the Sword and Sorcery genre. I could tell by the Frank Frazetta cover painting that this was the sort of thing I had enjoyed so much in Creepy. I had never been much of a reader before (it seemed to take forever to get through Freddy the Detective), but Howard’s tales of Conan instantly galvanized me! My Junior High (now they call it “Middle Schoolâ€) English teacher used to give us index cards to record the few boring novels they forced us to read, but I now asked for card after card to record the literally scores of titles by Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tolkien, Lin Carter, etc., that I was consuming. Oh I did my homework all right, all A’s, as a matter of fact.

It wasn’t long before, both my imagination and my love of reading being ignited, I widened my scope to other interests. Today I have two earned Ph.D. degrees. This trajectory began way back with Spider-Man. Spidey was a scientist, got his powers during an experiment with a radioactive spider. Believe it or not, this inspired me to want to become a research scientist. (Instead I’m a biblical scholar, but it’s still research!) And not long ago, one of the most exceptional students I ever had the pleasure of having in class told me that he got his life together and began to try to perfect himself more and more every day–after reading the origin of Spider-Man who taught him that with great ability comes great responsibility. (This maxim was coined by Stan Lee.)

I Only Know What I Read in the Funnies

So kids learn to love to read through the medium of comics, since the dazzling artwork provides a good dose of sugar to make the medicine go down. But what is the medicine? I have just anticipated one of them: moral education. All cultures have hero myths, and the use of them is to help us see life in certain terms, as if it followed a certain type of script. It isn’t obvious that right prevails, that nice guys finish first, but that seems to be the best pattern to have in mind as we face what might otherwise seem like chaos. If we can be taught to envy the heroic quest, to admire the kind of person who defends the rights of others, well then, little by little, we might just be able to reshape the world in that image. We might be able to live that way, though maybe not in Technicolor. In a day when there seems to be a strange sheepishness about teaching values to children, and when TV makes kids think adults are dolts, comic books might be a secret weapon for parents trying to sneak some moral nutrition past their children.

Something else one learns pretty fast in the comics is science, and science of all kinds. Even linguistics, philosophy. I remember learning from Superman that diamonds come from compressed coal. I learned that Prince Charming must originally have sought a girl wearing a fur slipper, and that, since the French words for “glass†and “fur†are almost the same, the fairy tale evolved. I’ve seen Nietzsche quoted a number of times, and Schopenhauer, and William Blake, and the Gospel of Matthew. You don’t find that on network TV. You can get quite an education reading those “funny books.â€

Â

Modern Mythology

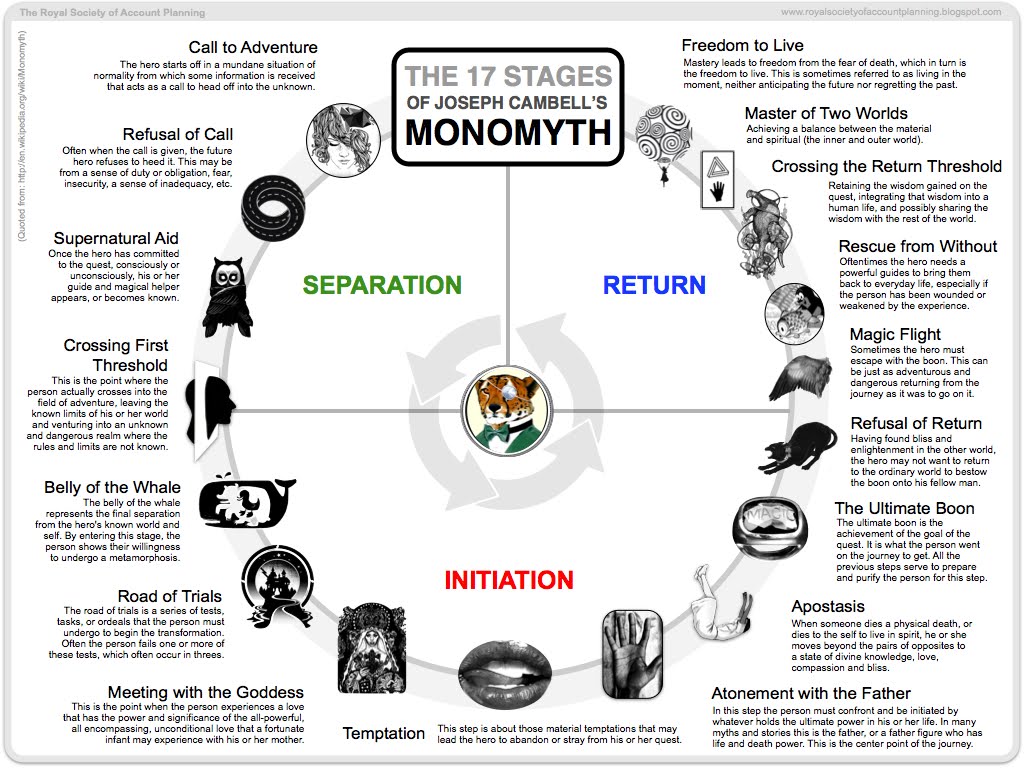

Why do we read stories, any stories? Superman or Gone with the Wind? William Tell or The Odyssey? I’ve already touched on this briefly, but it’s worth pursuing. We do learn lessons from inspiring examples, but it goes deeper than that. Joseph Campbell held that all stories ultimately boil down to hero stories. If you look deeply enough you can find the basic dynamic of a protagonist seeking some fulfillment, weathering setbacks, overcoming the odds, and winning through. These stories are as universal as the human race, and this isn’t coincidence, because the stories function as scripts that condition us to set and seek a goal and thus to create what no one else can give us: a purpose to life. We will, hopefully, begin to write, to live, our own version of the story, filling in the blanks as we see fit. If our lives are not about something, they will be a mere matter of marking time, filling our days at random. And this meaning is seldom if ever provided by some abstract idea, some concept, even a sublime one. No, meaning is provided by narrative.

And to get their point across, stories tend to paint with broad strokes, bold colors. Superman is, of course, Everyman. What do you think Clark Kent is doing there at all? He is the mundane exterior of every person. Superman is the amazing potential hidden inside us, so deeply hidden that sometimes neither we nor others ever discover it. But the point of the stories is to help us discover it. Occasionally a Superman story has the Man of Steel confounded, unable to defeat a challenge, only to discover that Clark Kent can win the victory by a less conspicuous route. Here the veil of allegory grows thin, and it is hard not to see the point: everyone is Clark Kent, and Clark Kent is Superman.   Â

If you have read Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, as everyone in my generation seems to have done, you may have gotten close to the end, read over a thousand pages, only to find an apparent anticlimax. You have accompanied Frodo, Aragorn, Boromir and the others to the Crack of Doom and back, overcoming the dread Sauron–only to return home to the Shire where a block-headed bunch of bureaucrats is in the process of tastelessly remodeling the place. The heroes thought they were home free and could rest by the fire. But no, there was block-headedness to be dealt with. Nothing cosmic, pretty laughable after dispensing with Sauron, right? But that’s the whole idea! We will never face Sauron, but we will face his small-scale counterparts of mundane evil, so mundane that we may not even think to call it evil. But these are the obstacles we must overcome with all the heroic endurance we can muster.

Joseph Campbell was a disciple of the great psychoanalyst Carl Jung, and Jung explained just how these heroic quest stories have their impact upon formative minds. It’s too bad Jung didn’t have a personal computer, because it would have made his point easier  to grasp. He taught that deep inside us there is a set of inherited images, “archetypes,†nothing spooky, just brain furniture, and that these images must emerge gradually from our deep subconscious into our conscious mind. If they don’t, we cannot mature. Some of the images are geometric and numerical: a square as a symbol of stability, the circle as a sign of wholeness. Others are basic literary characters, like the wise crone, who is embodied as the Fairy Godmother, the Gypsy Fortune Teller, your own grandma. The dragon, the hero, the prophet, etc. The archetypes appear over and over again all over the world and across the ages, in fairy tales, myths, scriptures, Buddhist mandalas, alchemist diagrams, Gnosticism, etc. We need ‘em. It’s as if the mind is a computer, and in order to learn how to use all the programs, you have to learn, one by one, what all of those icons on the screen mean. They are just iceberg tips, calling up the deeply-laid programs your computer was born with. They’re all there, but they won’t do you, the computer-user, any good if you don’t access them. Myths are there to present the subconscious icons, archetypes, to the conscious mind so you can click on them and get them running.

How do you activate them? There are two basic ways, and religion specializes in both. First there is ethics: like my student who read Spider-Man and realized he had to act responsibly. He was living into the archetype by his daily choices. Then there are rituals. Rituals are miniature symbolic psychodramas. They produce certain results in us by having us act out a myth in symbolic form. The actions of a ritual, like adult baptism, or chanting scripture in one’s Bar Mitzvah, are not themselves moral actions in the mundane world. Indeed, their very “strangeness†sets them apart in our minds and memories so they can have an impact on us that no mundane act would have. Religion offers us symbolic stories and ways of acting them out by which, Jung said, we can access the archetypes. This is why Jung disagreed with his teacher Sigmund Freud on the value of religion. Freud focused on the neurotic potential of religion and how it protracts childhood for those who retreat into God belief as an excuse for not thinking for themselves, not making their own decisions. Jung did not deny many people use religion for unworthy reasons and with bad results, but he thought Freud, ignoring the archetypes, failed to see how religion could actually help the psyche mature.

I suggest that in our day, when religious belief is for many no longer the simple matter it once was, when children grow up in homes with mixed faith or none at all, the modern myths of Wonder Woman, the Silver Surfer, Batman, and the rest have very much the same power of traditional religious stories. Granted, this is partly because the comic books overtly borrow from the Bible and from Greek and Norse mythology, but just as often they don’t. They are simply the same sort of thing. And comic books even have a kind of advantage over the traditional religious stories.

When we read comic books we know we are under no obligation to believe the events depicted there actually happened. This fact allows and even encourages the free soaring of the imagination. Comic fans often make up their own super-adventures, and even act them out (ritually!) with a towel for a super-cape. Nowadays there is “cosplay,†in which teenagers and adults dress up as their favorite superheroes at parties or fan conventions.

Some decide they could tell stories just as well or better than the pros whose work they read. And that’s how the next generation of comics creators emerge. In many religious communities, by contrast, the imaginative fire of even the most spectacular stories of scripture can be deadened, leadened, if the child (or adult!) is told he or she must believe the story really happened. In that case, the story becomes a clamp, a vise, something to restrict and imprison the imagination. But in the case of comics, there is no such dogmatic agenda. I am, remember, a Bible scholar. I love its stories and spend my life studying and expounding them. But they have become so sacred that we are often afraid to touch them, to treat them as stories ought to be treated. And one of the things scripture tells us is that our very soul, our selfhood, will be in peril if we do not keep alive the child within us. Comic books help us keep that eager child active within us, and if we start our children on these wholesome works early enough, we will be both guiding them into a healthy maturity and keeping the flower of their childlike spirit alive.Â

So says Zarathustra, super-fan of the Superman.

One Response to Spider-Man as Scripture