“Alienation†is perhaps most often discussed these days with reference to loners and other social outsiders, people who can’t fit in and suffer psychologically for it. But there are several other aspects of alienation that are equally important and deserve analysis (even if, as here, superficially and cursorily). Let’s consider a few of them one by one, then see what, if anything, they have to do with each other. I’m not guaranteeing they will.

Rene Girard (Violence and the Sacred), sociologist and literary critic, theorized that social order has emerged (and re-emerged) time after time from the chaos of class, faction, and caste conflict. To make a long story short, Girard envisioned a recurrent situation in which warring groups, jealous for each other’s prerogatives, reach a bloody stalemate in which neither side can honestly accept responsibility since each has become equally guilty of atrocity. There are only villains. Each side’s bitterness is justified (both have become “monstrous doubles†of each other). How are they to move past this impasse? Attention comes to rest on some outcast randomly chosen and accused of evil magic. It is he who is at fault! If he is eliminated, the fighting, the massacres, will cease. “Cast out the scorner, and dissension will go out†(Proverbs 22:10). Once he is done to death, the scapegoat is seen in a new light: as a supernatural savior! After all, by the simple fact of his execution he has brought peace where once was war. Both factions now reproach themselves for having put the savior to death, ignorant of his holy nature. To avoid a relapse into the War of All Against All, the reconciled society commemorates the “originary violence†by regularly repeated sacrifice (usually animal sacrifice) which, paradoxically, both recalls yet disguises the saving event.

The syst3em, which Girard posits as the origin of every religion, may break down. This happens if and when a sacrificial crisis occurs. The participants somehow or other become alienated from the sacrifice. It comes to mean nothing to them and thus no longer functions as a social pressure valve. A prime case of the sacrificial crisis leading to social collapse would be the cessation of the Jerusalem Temple sacrifices that led directly to the Jewish-Roman War in 70 CE. Jewish revolutionaries put the priests to the sword, seeing them as lap dogs of the Roman occupiers. This spelled the end of the sacrifices that had been daily offered on behalf of Caesar. And this cranked up the Roman war machine.

For some decades Jewish worshippers had been growing alienated from the sacrifices they offered. Remember the gospel scene in which Jesus enters the Temple and overturns the tables of the moneychangers and drives the animals from their stalls? Why were animals and currency exchange booths located in the Temple to begin with? Well, you had to sacrifice your sheep, and it had to be in perfect health. Suppose you brought Lambchop all the way from Galilee and he/she broke a leg somewhere along the way, not an uncommon occurrence. Or suppose the sheep had some flaw you didn’t notice? You were screwed! So, for your convenience, there were Temple personnel who would sell you a “government-inspected†animal on site. But what if you had only Roman denarii? Uh-oh. No good to use for sacred purchases! Those heathen coins bore “idolatrous†profiles of Caesar. You could use them to pay Roman taxes, but God wouldn’t touch ‘em with a ten foot shepherd’s crook! (Hence “render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s and unto God that which is God’s,†Mark 12:17.) So the average worshipper was doubly distanced (alienated) from “his†sacrifice: it wasn’t really his sheep. It wasn’t from his flock. And he hadn’t even been able to buy it with his own money! The sacrifice had become a charade. “I will not offer to Jehovah that which costs me nothing!†(2 Samuel 24:24; 1 Chronicles 21:24). It reminds me of Tibetan prayer wheels: you just set them spinning as you walk by. Are you praying by remote control?

There is also a sense in which alienation is fundamental to social order. This one is explained by Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann in The Social Construction of Reality. Here alienation is a phase of a process by which the ingenious inventions of human beings like ourselves are subsequently elevated to the stature of divine creations with unimpeachable authority and majesty. In the beginning of a civilization the wise elders see the need for rules and laws in order to maximize peaceful coexistence. You have to eliminate as much theft, murder, rape, etc., as possible if you want to make any progress. Those who frame these laws and customs know good and well the ad hoc nature of their creations, but the next generation inherits these rules as a reality external to and prior to themselves. Thus the social arrangements appear with a new gravity they had not originally possessed. Perhaps they will even come to be deemed God’s commandments fresh from Mount Sinai.

What has happened here? Human beings become alienated from their inventions so that they become objectified, then reified. Reification means that arrangements designed by humans for humans are transformed into self-perpetuating realities served by humans. Someone who saw what was going on once said, “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath†(Mark 2:27). Once people do start to realize this, perhaps by reading Berger and Luckmann, respect for the traditional norms declines. “What? You mean the Constitution was written by rich white guys to feather their own nests?†The eventual result is called anomie, normlessness, and, again, the War of All Against All.

This is what Socrates was fighting against. The Sophists had traveled outside Athens and discovered that all the city-states had different codes, all of them ascribed to the gods. For them, the jig was up. They taught relativism. And Socrates was attempting to reestablish some objective standards of truth and meaning.

Why do people who live off government largesse often take it for granted? Because they have no investment in it. They did not earn it by their own labor (even if their disability made labor impossible), so they cannot value it. Given free housing, the poor may not take care of their homes because they have nothing invested in them, either. It is alienation. Similarly, students value their education if they have to pay for it. If they don’t, they may not think it worthwhile to put any work into it. I have certainly observed that in the classroom. Again, it is alienation.

More alienation: Karl Marx wrote about the alienation of industrial laborers from the product of their labors. Where once artisans could take great satisfaction in what they produced, pointing to a plow, a painting, a garment, and saying, “I made that!†the assembly line wage-slaves of Capitalism had but a nominal connection to what they collectively produced. “I’m just a cog in a wheel, Jody. … In one bomb there are perhaps a thousand pieces. Every piece requires a team of fifty, sixty, seventy people.†(Richard Matheson and Rod Serling, “Third from the Sun,†The Twilight Zone, January 8, 1960). The alienation here is quite similar to that at stake in the crisis of sacrifice. In both, what the individual offers/produces is no longer really his own. A hidden, vital link has been severed. And because of it, the individual’s efforts are empty. But is Socialism any better? In the Socialist Iron Curtain countries, the work ethic was vitiated by the realization that one’s work, done well or badly, would not increase one’s wealth but would only vanish down the bottomless toilet of the “collective good.†Is this alienation really any different from or better than that produced by industrial Capitalism?

“I’d like to change the world but I don’t know what to do, so I leave it up to you.†In the meantime, is there anything that can be said about the individual looking out on this dreary landscape? I think of one more type of alienation that might come in handy, and I find it in the Bhagavad Gita. There we read of something called karma yoga. It is a type of religious devotion in which one offers one’s everyday work as a sacrifice to one’s chosen god. One obeys the dictates of one’s dharma, the set of occupational duties dictated by one’s inherited caste. But one does not perform them with ordinary motives, legitimate though they are, e.g., putting food on the table. Instead one “acts apart from the fruits of action,†transforming the mundane into the sacred by consciously directing it to Krishna (or whomever) as if daily actions were ritual sacrifices performed by Brahmin priests. This can be seen, I say, as a type of voluntary alienation from the product of one’s labor, via sublimating it into something else, something spiritual.

I believe there is also a less overtly religious version of this karma yoga, and this version is well represented in the movie The Legend of Bagger Vance, which is a demythologized version of the Bhagavad Gita, as the name itself reveals: “Bagger Vance†= “Bhaga Vad.†Anyway, Bagger appears out of nowhere to help retired golfer R. Junnah (the Arjuna of the Gita) regain his rusty skills in preparation for a big tournament. Yes, he does want to win, but the essential thing Junnah needs to learn is that he must play the game for the sake of the game, regardless of the outcome. That is to act without the fruits of action.

In this demythologized understanding of karma yoga, we leave behind the ironclad caste system of inflexible social stratification and recognize instead what I believe to be the underlying and genuine meaning of dharma. Your dharma is the law of your own being as dictated by your inborn talents, interests, and loves, wherever they came from. It is another name for what Aristotle called your entelechy, the “thing†that makes the acorn develop into an oak rather than a stalk of celery. That which makes you, but not the guy next to you, want to become an artist or a trumpet player. You will not be happy doing anything else, and this inclination probably attests a natural talent, or you’d be inclined to do something else. And as you pursue the direction set by your own nature you will not be doing it as a mere means to an end but rather as an end in itself. That is voluntary alienation from the “cash value†of your work.

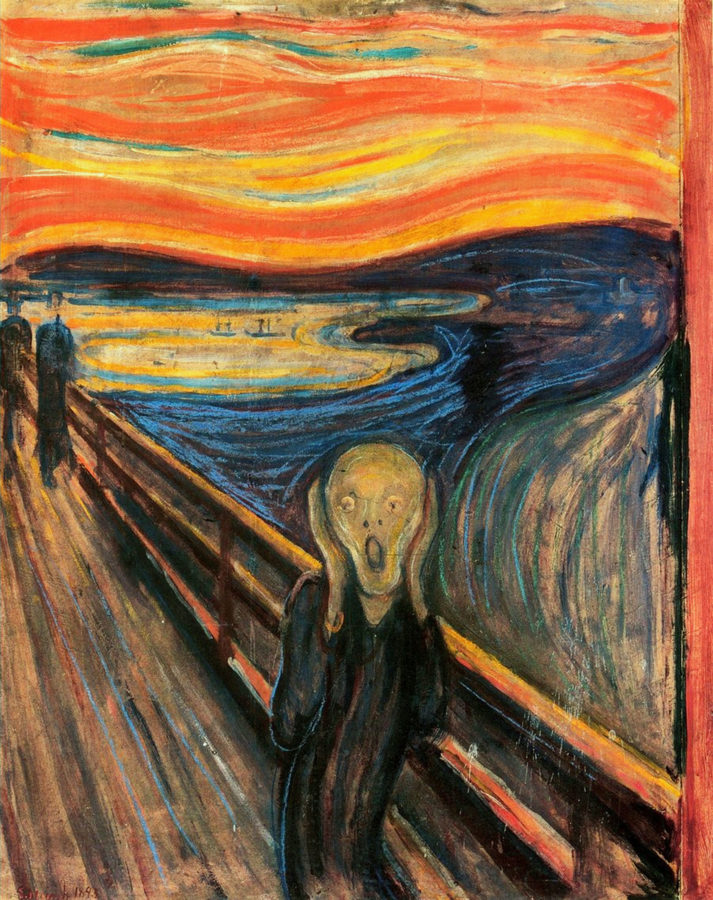

But suppose circumstances prevent you from the free pursuit of your nature. It happens. Plenty. Here I think of Camus’s brilliant essay “The Myth of Sisyphus.†Sisyphus was sentenced by the Olympian gods to while away eternity in Hades by pushing a huge boulder up to a hilltop, whence it must forever roll-bounce back down, whereupon the doomed man must retrieve it and struggle it up the hill again—all to no purpose. That’s what I call alienation from one’s labor! But Camus saw that even in, and especially in, such circumstances (i.e., the real-world conditions thus symbolized) there is possible a higher alienation: the determined resistance of the human spirit, the attainment of an inner freedom transcending circumstances by a sheer attitude of heroic defiance.

So says Zarathustra.

One Response to Alienated