My Two Dads

Carol and I were watching The Rifleman this morning. It’s still on as I write. I watch an hour of it every day. Ditto The Andy Griffith Show. There are significant parallels between the two shows’ premises. Both center on the adventures of a widowed father who is a lawman (Rifleman’s Lucas McCain is often deputized or serves as fill-in marshal). Both run through a series of girlfriends but never remarry. Each is a great dad, raising his young son without a mother. There is a surrogate mother character in each show: shopkeeper Hattie in The Rifleman, Aunt Bea in Andy Griffith. (The same actress who portrayed Hattie went on to play Clara Edwards, Aunt Bea’s best friend!) The Rifleman premiered in 1958, Andy Griffith in 1960. I guess it’s possible for the one series to have borrowed from the other, but I doubt it.

Lucas McCain is much like Star Trek Captains Kirk and Picard. The Rifleman exemplifies unimpeachable character and integrity, together with a sense of duty to his own code of honor as well as to his community. He has courage and can back it up with power. He is a forgiving Christian, eager to believe the best about people and to give them a second chance. Each episode is a morality play with a lesson to teach, yet without sanctimonious priggishness. The story is always told for its own sake, but given the kind of person Lucas is, any stories told of him must contain moral lessons. I wish parents and schools would have kids watch The Rifleman, both as a set of history lessons and as character education.

But that’ll never happen.

Why? Because most episodes end with Lucas shooting down the bad guys, albeit in self-defense. Even in its initial run, some condemned the show as the most violent on TV. How much more objectionable the gun violence must seem to Politically Correct pantywaists today when little kids get suspended from school for pointing fingers as imaginary guns! And that’s too bad since such prissiness fosters the nonsensically naïve notion that guns are not necessary to ensure a safe society. But they still are, just as in the 1880s. There are two episodes that face this problem directly, showing how attempts to control crime by confiscating firearms wind up inviting the very chaos they aimed at avoiding. The show makes the point loud and clear: the righteous as righteous must be prepared to kill the wicked—lest they become the wicked by neglecting to prevent their wicked deeds. It takes courage. And courage is a virtue.

Sheriff Andy Taylor is quite different on this point. Like an English bobby: he does not usually carry a gun. Like that of his transatlantic counterparts, Andy’s policy presupposes a civilized society whose crimes are not usually violent and thus do not require a violent response. Andy does take a rifle off the rack on those rare occasions when an escaped criminal from the outside world infiltrates the mini-Shangri-La of Mayberry. But, as I remember, he has never had to fire it.

Andy takes turns teaching, usually Socratically, character lessons to his son Opie and learning from the boy who doesn’t hesitate to point it out when the Emperor of Mayberry has no clothes. As the years passed, the character of Andy became even more morally upright, no longer the truth-stretching rascal he was in earlier seasons. Unfortunately, he became a bit of a bore. When he finally left the show for a new series, Headmaster, where he was in charge of a private school, the transition seemed too completely smooth.

Some Iron in Your Diet

But it is not just character lessons in general that such TV shows teach, as important as they are. Without trying to, these shows illustrate what it is we increasingly lack in early twenty-first century America: normative nuclear family structures and the dynamic relations between relatives that we evolved to depend upon. A terrific book setting forth these relations is poet Robert Bly’s Iron John, very popular in the 1990s. The title refers to one of Grimm’s Fairy Tales in which the King drains a swamp in which a furry anthropoid (think Bigfoot) lurks. The locals fear this creature, called Iron John. The soldiers manage to take him captive and to place him in a cage, where he poses no danger and serves as a spectacle for the curious. One day the child Prince is playing with a ball which rolls into Iron John’s cell. The giant offers to return it to him if the Prince will fetch the key to the cage, which is kept under the Queen’s pillow. This is a dicey proposition because the King has decreed that anyone who releases the Wild Man will be executed. The boy goes ahead with the scheme and manages to filch the key. He frees Iron John and, afraid his crime will be discovered, leaves with Iron John. They live in the forest, where it turns out Iron John guards a vast hoard of riches and relics stored down a well. The man-monster must go away on various errands, leaving the prodigal Prince minding the store. He charges him never to enter the well, but eventually the boy accidentally falls partly over the edge. This turns his hair to gold.

Iron John sees what has happened in his absence and sends the lad away, deciding it is time for him to leave Toyland and enroll in the School of Hard Knocks. So the Prince hits the road. Eventually, he enters the service of a foreign king. He proves his mettle in battle, then wins the hand of the king’s daughter. Finally, he is reunited with his parents at the royal wedding. Iron John shows up, too, but he no longer looks like a Yeti. He is a glorious, golden king, freed from a curse which had transformed him into his apish form until he should find someone worthy of freeing him.

Bly saw in this tale, quite plausibly, a lesson of male maturation. The central character is not really the boy who matures but rather his initiator, without whose guidance and challenges the youth cannot mature. A male mentor (father, uncle, coach, whatever) separates a lad from his mother’s doting care. He helps the boy to discover his male energy, what Bly calls his “Zeus energy.†It is power, ferocity, animal instinct. The young man must by no means suppress his urges but instead learn to find their proper place, the right times and occasions in which to manifest them. The ideal would be a man who is quick to show compassion but from a position of superiority. One for whom a compromise is condescension rather than surrender, who is “big enough†to forgive; i.e., he forgives freely, not because he is obliged to do so.

In our bizarre era, male mentoring has become more and more rare, and this is the result of the breakdown of the family unit. On the one hand “Great Society†programs have gutted ghetto families by invalidating the husband-father’s labor by making government assistance easier and more lucrative than working at a job. No longer needed and feeling useless, these men are robbed of their natural dignity and abandon their families. Their male children have no adult male to assist their transition to maturity. Their Zeus energy has to go somewhere, so these kids join violent street gangs, seeking legitimation, affirmation, i.e., respect, through crime, proving their valor by daring but destructive exploits.

On the other hand, in the hands of feminist ideologues, young men are urged toward “androgyny,†i.e., emasculation, feminization, sissification. Their Zeus energy is extinguished along with any idea of heroic achievement, of individual greatness that earns its stature above the faceless collectivity.

Woodman, Spare That Tree!

Neo-Freudian Jacques Lacan speaks of socialization as the imposition by society of “the law of the father.†Individual identity depends, ironically, upon definition in terms of the culture one is born into. And Robert Bly is, I think, affirming the importance of that patterning. But I believe his approach is predicated on the rejection of one of today’s regnant dogmas, that gender identity is a purely arbitrary social construction with no necessary relation to biology. By contrast, Bly presupposes the existence and importance of biologically assigned and essential maleness and femaleness. If these are neglected or allowed to go out of control or are denied by fiat, there will be destructive consequences to the individual and to society. Biology is destiny, as Freud said, at least insofar as it provides what Aristotle called an entelechy, an inborn tendency which may or may not be fulfilled, depending on external circumstances. The entelechy of an acorn is to become an oak, which it will actually do if not thrown off track by some tree disease or by a guy with an ax. Likewise, males are born with maleness, females with femaleness, gays with gayness, and to reroute that train somewhere along the line will most likely cause a trainwreck.

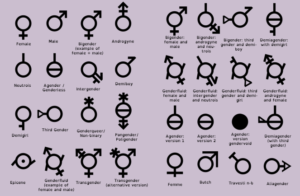

A rival vision is that of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (in their Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia), who issue a call to freedom, a deconstruction of the indoctrinated law of the father, giving birth to a kind of Dionysiac schizophrenia. This is what the Politically Correct Radical Left is promoting when they seek to dissolve traditional family structure, marriage, and gender identity. You can, they say, decide what gender you are, and some offer over fifty boxes to check. One may even, they say, choose which race to belong to, and this from the same ideologues who complain about “cultural appropriationâ€! They force (on college campuses) the adoption of artificial gender-neutral pronouns.

Ultimately these trends must create a condition of anomie, normlessness, moral and political anarchy in both individuals and society. I contend that such freedom, which is but a euphemism for “nothing left to lose,†is Nihilism. It creates a mind that is so open that it needs to be closed for repairs. Integrity means you’ve “got it all together,†that your thoughts and actions are in harmony and that your values are consistent with one another, and with certain underlying principles. I submit that it is not possible to have moral character, hence personal maturity, if one lacks such a foundation. Thus I think it should be no surprise that today’s Leftists embrace the utterly cynical tactics of the devilish Saul Alinsky. “By any means necessary.†Uh, necessary for what? For the “freedom†that is really just an epileptic spasm? We are already feeling the sea-sickness from the ship pitching on the agitated ocean.

So warns Zarathustra.

2 Responses to The Law of the Father