The medieval Arab philosopher Averroes (Ibn Rushd, 1126-1198) is known for propounding the Double Truth theory, though he probably didn’t. That was most likely a polemical distortion by his opponents. But the theory is interesting in any case. The idea is that a thing may be true in the sense that philosophy, unaided reason, would logically lead to it, but false in that it runs afoul of official religious dogma. This is not quite the same thing as Aquinas saying that, for instance, though there is no intrinsic reason the universe could not be thought to have existed eternally, we can dismiss the possibility because Scripture reveals that it was created by God at a particular moment of time. In that case, it is just that, in the absence of definitive proof, we are left to speculation—until an answer comes from a different quarter. As I understand the Double Truth theory, it envisions a contradiction between reason and revelation, not just revelation picking up where reason leaves off. Double Truthism seems to intend that, even though revelation (i.e., dogma) disallows or condemns an idea, there’s still an alternative zone of some sort in which it can be considered true. It’s a clever dodge, and opponents of the idea were not slow to realize this. Nice try, but no cigar.

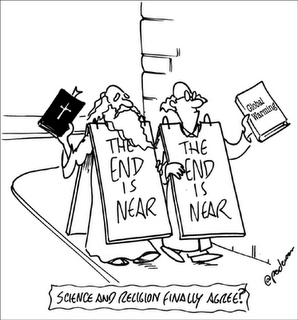

In case this sounds familiar, you might be thinking of the recent contention of evolutionist Stephen Jay Gould that science and religion are “non-overlapping magisteria.†Gould was trying to stultify the old “religion versus science†debate by saying it had all been a big misunderstanding. Like that episode of The Andy Griffith Show in which Sheriff Taylor settles a generational feud between two backwoods families by demonstrating that the old offense had never actually happened in the first place.  As Weekend Update commentator Emily Litella used to say, “Oh! That’s quite different! Never mind.†Gould made the big announcement that religion and science are talking about totally different things. Religion is not concerned to make factual assertions. Science is. They’re not working the same side of the street. Nothing to fight about, see? Let’s shake hands and go our separate ways.

As Weekend Update commentator Emily Litella used to say, “Oh! That’s quite different! Never mind.†Gould made the big announcement that religion and science are talking about totally different things. Religion is not concerned to make factual assertions. Science is. They’re not working the same side of the street. Nothing to fight about, see? Let’s shake hands and go our separate ways.

But there was nothing new here. Paul Tillich, who actually knew what he was talking about, had explained it all decades before in books like his Dynamics of Faith, where he described the “intellectualistic distortion of faith,†the definition of faith as assent to certain fact-claims. Faith that Charlton Heston parted the Red Sea or that Max von Sydow rose from the dead is not proper faith. Believing that so-and-so happened when it cannot be proven from definitive evidence ultimately produces fanaticism and intellectual dishonesty, pretending you are certain of something when you have no right to be. If you admit it is impossible to be sure that certain ostensible events ever occurred, but you believe faith requires such certitude, you are in for endless torment. Forget about peace. You will forever fear that some discovery or argument will undermine your faith. “So far, so good! Nothing too threatening in the Dead Sea Scrolls thus far! I’m safe for the moment…†What kind of faith is that? Something is wrong here. What is wrong is that faith is rightly understood as ultimate concern, the never-ending struggle of Jacob with the angel. Genuine faith, Tillich explains, is compatible with doubt and even presupposes doubt—because faith is existential commitment, not affirming a set of historical assertions. Faith should have no vested interest in any particular scientific theory or historical reconstruction.

What’s the difference between Tillich’s view and Gould’s? Simply that Tillich admitted he was trying to correct most believers’ conception of faith, while Gould pretends (or thinks) he is just describing people’s faith as it is. Gould is employing an old rhetorical trick: seeming to describe when he is actually prescribing. It is to short circuit the argument, to beg the question. Pretty sneaky. People do not understand their faith as indifferent to questions of fact (science and history). Gould, like Tillich, wishes people did understand faith as these sophisticates do, but Gould is in effect trying to persuade them that they already do.  He is trying to win the war by subterfuge, by seeming to surrender. Again, he is trying to describe faith as a different language game, which believers do not think it is. John Warwick Montgomery wouldn’t let people like Gould get away with this stratagem. You may think religionists should view faith this way, but that’s not how they do view it. It’s the same strategy it was in Averroes’s day: “We’ve got the real truth, but feel free to call your nonsense ‘truth’ if you want. Just stop bothering us, okay?â€

I see yet another version of the Double Truth gimmick in the field of New Testament studies. The late, great Raymond E. Brown was above board about this. He admitted that there was inadequate basis for certainty on matters such as the virginal conception of Jesus. Purely as a historian, he had to admit that the story was improbable, a toss-up. But as a Roman Catholic priest, obedient to the doctrinal authority of the Church, he professed his faith that Jesus was indeed miraculously conceived without a human father. He understood he was drawing upon two entirely different epistemologies, each appropriate to one of the hats he wore. He did not try to pass off a leap of faith as a historical judgment.

Evangelical Protestants do not believe themselves duty-bound to any ecclesiastical party platform, but they do have their own version of the Double Truth model. Their a priori, controlling axiom is the authority of Scripture. This article of faith controls and dictates what they pretend are simple, honest historical judgments. As Tillich already had plenty of occasions to see, they could not admit, even to themselves, what they were really doing: apologetics on behalf of a stacked deck of theo-historical assertions. Van A. Harvey distinguishes the two hats between which the scholar must choose to don: the historian or the believer. Apologist William Lane Craig argues for the historical resurrection of Jesus based on a (contrived) presentation of the evidence as if a Buddhist, an atheist, and a Rastafarian should equally find it objectively compelling. Yet he admits that it will take the subjectively seductive influence of the Holy Ghost to bring one around to Craig’s “truth.†He’s just damn lucky that the gentle whisperings of the Paraclete just happen to come to the same conclusion as his so-impartial scholarly judgment.

It is a voluntaristic commitment to biblical inerrantism that controls the apologists’ “historical†judgments, what amounts to a second and superior source of historical information. I can only compare this Double Truth epistemology to that of Rudolph Steiner and Edgar Cayce, whose clairvoyant visions supplied them with “information†about Atlantis, Lemuria, and (of course!) the ministry of Jesus Christ “missing†from all historical records.

Perhaps the Double Truth duplicity is most sharply drawn from this angle. Are you open-endedly seeking the truth with no particular hoped-for outcome? Or are you pushing for a favored result? Are you prepared for ever-revisable, always tentative, only-provisional results, never reaching definitive certainty? Or will nothing less than a once-and-for-all verdict satisfy you? Your answers to these questions will reveal whether you are really a researcher or rather a mere apologist, a spin doctor with a conflict of interests.

A double truth is no more the Truth than is a half-truth.

So says Zarathustra.

3 Responses to An Aversion to Averroes