I don’t know if you will be familiar with the name or the thought of Friedrich Schleiermacher, and if you’re not, that helps prove my point: that this nineteenth-century thinker (one of my greatest heroes) had something to say about religion that clarified it in his day and would clarify it again today if it were more widely known. He was the first to turn the Wheel of Dharma for theology after the Copernican Revolution in epistemology wrought by Kant. Let’s back up.

I don’t know if you will be familiar with the name or the thought of Friedrich Schleiermacher, and if you’re not, that helps prove my point: that this nineteenth-century thinker (one of my greatest heroes) had something to say about religion that clarified it in his day and would clarify it again today if it were more widely known. He was the first to turn the Wheel of Dharma for theology after the Copernican Revolution in epistemology wrought by Kant. Let’s back up.

Immanuel Kant, raised as a Lutheran Pietist in the century before Schleiermacher, demonstrated the impossibility of gaining true knowledge apart from the senses (and the processing of sense data through our built-in array of the Categories of Perception and the Logical Functions of Judgment). There could be no “revealed knowledge†such as theologians had always claimed as the indispensable basis of their doctrines. So what sort of reconstruction of religion might be possible?

Kant himself (like Hegel, I believe) viewed religion, with its miracle stories and ancient myths, to be essentially a symbolic language for morality. If all that stuff helped you learn the lessons of righteousness, great. But if it became an end in itself, if it distracted from morality, or worse yet, as in the devastating wars of religion (still fresh in memory in Kant’s day and new again in our own), if it prompted horribly immoral behaviors, then to hell with it. Religion was like a cartoon version of morality for children, and eventually the time arrives to put away childish things. So Kant decided that “enlightened piety†consisted in morality. Ethics is the essence of religion.

Schleiermacher believed Kant was right about the unavailability of extra-sensory knowledge, the lack of revelation. But he could not agree with Kant’s view of the essence of religion. In his view, Kant had reduced religion to ethics. Just ethics? Sure, morality is indispensable, non-negotiable in importance. But if religion simply boils down to morality, religion is revealed as superfluous. And Schleiermacher thought that completely inadequate. Kant was selling religion short. He had missed the essential thing about religion. And what was that?

Schleiermacher distinguished between three aspects of religion. First was knowledge. This was information about God and his unseen world. It could not be discovered but had to be revealed. But, in the wake of Kant, it turned out there was no such knowledge. The second was practice, specifically ethics. We have seen how Kant subtracted knowledge, emptied that category. Ethics was what was left of religion. Schleiermacher thought Kant had jumped the gun, skipping a third aspect of religion, one which should now be recognized as the essential aspect, in fact, the very essence of religion.

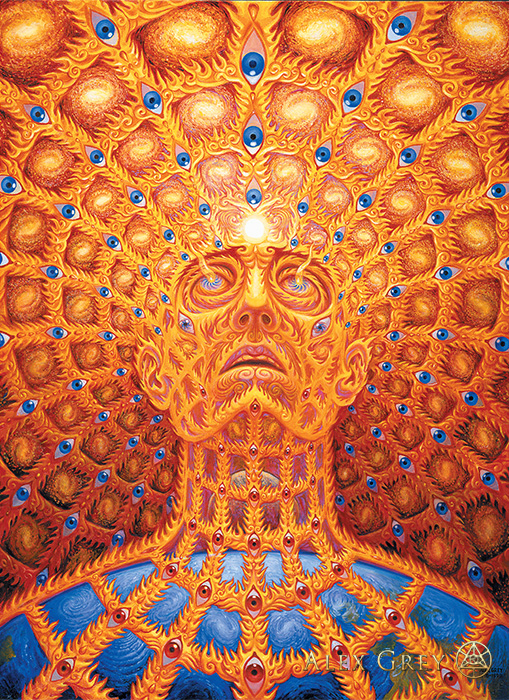

That aspect is piety, which Schleiermacher defined as “a sense and taste for the Infinite†and “the feeling of absolute dependence†upon the great totality of Being, God understood in pretty much a Pantheistic sense (Schleiermacher was much influenced by Spinoza). Schleiermacher explained that all life is contingent upon a web of many factors: your parents happening to fall in love, your food not being poisoned, the roof above you not falling in, etc. And much depends upon you in turn. We are all relatively dependent upon all these factors, but upon the great overarching Whole each of us is absolutely dependent. Everyone is, but not everyone lives in conscious, grateful awareness (“feelingâ€) of it. Those who do are pious in Schleiermacher’s sense. This awareness is intuitive, a thing more fundamental than cognitive knowledge, i.e., knowledge of discrete things, available to us through the senses.

That aspect is piety, which Schleiermacher defined as “a sense and taste for the Infinite†and “the feeling of absolute dependence†upon the great totality of Being, God understood in pretty much a Pantheistic sense (Schleiermacher was much influenced by Spinoza). Schleiermacher explained that all life is contingent upon a web of many factors: your parents happening to fall in love, your food not being poisoned, the roof above you not falling in, etc. And much depends upon you in turn. We are all relatively dependent upon all these factors, but upon the great overarching Whole each of us is absolutely dependent. Everyone is, but not everyone lives in conscious, grateful awareness (“feelingâ€) of it. Those who do are pious in Schleiermacher’s sense. This awareness is intuitive, a thing more fundamental than cognitive knowledge, i.e., knowledge of discrete things, available to us through the senses.

Schleiermacher thought we could draw certain inferences from our subjective religious experiences, experiences of “God.†These would count as “knowledge†only in the sense Kant described as the fruit of “practical reason†as opposed to “pure reason.†This was the way Kant arrived at his “practical†argument for God’s existence. Technically, Kant admitted, we cannot know there is a God, but if there is no God to guarantee moral standards, then the whole thing is an illusion. Are we really prepared to accept that? It seems a better bet to proceed on the working hypothesis that there is a Creator who instilled within us the universal moral law and provides an afterlife in which our character development may be brought to completion. This is, roughly speaking, the kind of inference Schleiermacher thought we can derive from religious experience, from “God-consciousness.â€

So what’s the difference between Kant and Schleiermacher on this point? For Kant, this experiential argument was just a way to secure a reason for morality, while Schleiermacher saw it as a source from which some sort of religious doctrines might be derived. To use traditional terms, Schleiermacher was willing to be satisfied with faith and not to lay claim to genuine knowledge. Henceforth, for Liberals, theology was no longer a matter of systematizing revealed knowledge (e.g., from scripture), but rather of interpreting religious experience.

But soon after Schleiermacher, Liberal Protestantism took a more purely Kantian direction, defining religion as essentially moral. Albrecht Ritschl, the second founder of Liberal Theology, moved the rudder, and the result was the influential Social Gospel Movement championed by Adolf Harnack, Wilhelm Herrmann, and especially Walter Rauschenbusch. As I understand the current religious climate, Liberal (what used to be called “Mainstream†or “Mainlineâ€) Protestantism as represented by, e.g., the Episcopal Church, the Presbyterians, the United Methodists, the United Church of Christ, and the American Baptists, have moved much, most, or all of the way in the direction of Rauschenbusch, Ritschl, and Kant. Religion has become essentially moral, specifically political. For these denominations, Christianity has become a subset of the Democratic and Green Parties.

As you know, much of Conservative Protestantism has likewise become heavily politicized. I believe that only a tiny fringe repudiated by the vast majority even of fundamentalists wants to impose a theocracy, a Christian counterpart to Islamic Sharia (though I have heard of a small movement of radical Christian theocratic terrorists in Latin America).

For the purposes of the point I am trying to make here, let me distinguish Conservative and Liberal political Protestantisms this way. The Conservatives still (erroneously) believe there is revealed information, infallible commands from a deity. This would seem to make them more potentially dangerous than their Liberal counterparts, but in fact there turns out to be little practical difference since Liberalism is not Libertarianism. Liberalism tends to impose, to regulate, to centrally plan, to patronize, to ostracize and vilify because the end is held to justify the means.

That is the ironic result of “situation ethics,†once a banner of personal freedom. This is the same danger inherent in the larger approach of Teleological ethics, which seeks to escape/avoid the legalism of Kantian Deontological ethics. Results, not rules, make an action right.

But there is an ironic vestige of the otherwise discarded faith that “calls things that are not as though they were.†We expect Liberal Protestantism, in the wake of Harvey Cox’s The Secular City, to be pragmatic, bare-knuckled, disabused of illusion in its pursuit of its social ideals. But there remains a worrisome Hegelian confidence in humans’ ability to discern what God is up to in the unfolding of history and whose side he is on to achieve his aims. That is implicitly theocratic, isn’t it?

And this species of hubris begets another: the faith that ignores likely consequences and that acts against the odds, assuming a diplomatic stance of “believing all things†that one’s nation’s enemies may promise one. That is no more noble, and is considerably more dangerous, than the “faith†by which Jim Bakker pursued various construction projects for which he lacked the funds, believing God would send him the money. I call it “political snake-handling.â€

Is there a contemporary version of what Schleiermacher called piety? I should think

devotees of contemplative prayer, “practicing the presence of God,†would qualify. They are certainly striving for God-consciousness. But, within the Christian fold, those who take this approach are more likely to be Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox. I am dealing with Protestantism here, the quadrant of Christianity Schleiermacher lived in.

As Unitarianism represents the extreme of the Kantian religion-as-morality trajectory, I should call New Thought (much of which has gone beyond specifically Christian symbolism) the stripped-down version of Schleiermacher-style religion. Of all Christian varieties, New Thought believers focus most clearly on a rather abstract, near-pantheistic God understood as a universal Source of abundance. One strives to remain open and receptive to that fund of endless possibility. This spirituality combines the feeling of absolute dependence and constant God-consciousness.

Nor is this a matter of coincidence, or of reinventing the wheel. It is instead a case of heredity. You see, New Thought owes a significant debt to the New England Transcendentalists and their belief in the Oversoul. And the Transcendentalists’ great source of inspiration was–guess who? Schleiermacher. New Thought seems to me the last redoubt of Schleiermacher’s spirituality. It may be judged a bit debased, often reducing God to a genie to conjure with, but even then it is refreshing in its lack of the hypocritical pretense to “radical discipleship” made by some political Christians.

So says Zarathustra.

2 Responses to Schleiermacher’s Forgotten Religion