Leonard Nimoy’s death (yesterday as I write) was an awful blow, though no real surprise after his recent hospitalizations. I doubt if there could be a better eulogy for him than the one Admiral Kirk delivered at the end of The Wrath of Khan. It may sound as if I have lost any ability to distinguish between Mr. Nimoy and the character he portrayed to such great effect. And I suppose I have. But it’s Nimoy’s fault. Leonard Nimoy brought the Spock character to life in an almost literal sense. Just after the bone-headed NBC cancellation of Star Trek (just as tragically inane a move as CBS’s turning down the show in favor of the insultingly stupid Lost in Space),Â

Leonard Nimoy’s death (yesterday as I write) was an awful blow, though no real surprise after his recent hospitalizations. I doubt if there could be a better eulogy for him than the one Admiral Kirk delivered at the end of The Wrath of Khan. It may sound as if I have lost any ability to distinguish between Mr. Nimoy and the character he portrayed to such great effect. And I suppose I have. But it’s Nimoy’s fault. Leonard Nimoy brought the Spock character to life in an almost literal sense. Just after the bone-headed NBC cancellation of Star Trek (just as tragically inane a move as CBS’s turning down the show in favor of the insultingly stupid Lost in Space),Â

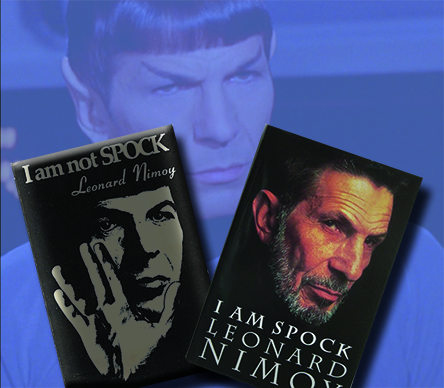

Nimoy wrote a book titled I Am not Spock, hoping to avoid being typecast, or, really, being obscured and absorbed by the character he played. But that is just what happened. (Come on! The cover of that very book had a photo of the actor making the Vulcan “Live long and prosper†hand sign!) Actually, Nimoy wasn’t type-cast. He played various roles over the years on Mission Impossible, In Search of, and Fringe. But he knew good and well what had happened decades later when he published a second book called I Am Spock. He was.

I think of moments from two non-Nimoy movies. In Batman Begins, Ras al Ghul tells Bruce Wayne that, in order to fight crime as he wants to, he must “become more than a man.†In Captain America: The First Avenger, Steve Rogers returns to camp having liberated hundreds of soldiers from a Nazi work camp, and Bucky Barnes exhorts the crowd, “Let’s hear it for Captain America!†In that moment, Steve has become a living symbol, something “more than a man.†It tells us the crucial thing about the myth of comic book super-heroes: that we have the possibility to transcend mere individuality. Not in the wretched collectivist sense, merging into the mass, which is to become less than a man. Rather, it is to incarnate a myth and an ideal. Not just a patriot, but Uncle Sam.

This is what Paul Tillich said characterized the person of Jesus as the Christ: he had sacrificed what was Jesus in him to what was the Christ, the Anointed. In Jungian terms, one could say that Jesus had become a Christ figure! And he had done so by virtue of “the inflation of the archetype,†becoming lost in the Christ Archetype (already available in the Collective Unconscious).

Anyone remotely familiar with the Star Trek episodes and movies knows that Mr. Spock was a Christ figure. Nor was this simply a matter of his death and resurrection. Throughout the series he had been a perfect blend of spirit and reason, of cross-bearing and selfless duty. He was a kind of demigod along the lines of the Jesus of Matthew and Luke, not a divine incarnation but rather a hybrid of heaven and earth. In Spock’s case, the “heavenly†half was his space alien heritage as half-Vulcan. (Keep in mind that in the Bible, “heaven†simply denotes “the sky.†Jehovah was what we would call a space alien, much in the manner of the God-entity in Star Trek V.)

Star Trek’s Romulans and Vulcans were supposed to share a common origin, diverging after Vulcans colonized what would come to be known as Romulus (at least I think that’s the history). Once they went their separate ways, the Romulans symbolized the martial ethos of the Roman Empire (the Klingons, on the other hand, are the Mongol hordes). The Vulcans represent the Roman Stoicism of Cicero and Seneca. Spock is the perfect Stoic, setting aside emotion in favor of dispassionate reason. But Spock and his fellow pointy-eared philosophers also display elements of Zen Buddhism, as when in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, Spock explains that he displays Mark Chagall’s painting of the expulsion from Eden to remind himself of the fleeting character of all things: that’s the Buddhist tenet of anicca, impermanence. Vulcans are sometimes depicted in Roman togas, sometimes in Zen monastic robes. A key moment in The Wrath of Khan is when Kirk finds Spock in a black Zen robe meditating in his quarters. (Zen is even more prominent in Star Wars, no great surprise given the Japanese cinematic inspiration of that movie.)

All this suggests that perhaps Trekkies are not quite so pathetic as they seem. I love Star Trek very much and have watched it avidly since the very first season of the show in 1966. I’m talking about fans who dress up in Starfleet uniforms and Klingon armor, the geeks depicted on that classic SNL skit with William Shatner telling off a room full of pimply conventioneers wearing Spock ears. This creeps me out big-time. To me, such antics suggest an inability to find meaning in the mundane world, though I could be wrong.

Yeah, maybe I could be at that, because here you have a bunch of people who are so inspired by the world of Star Trek that they wish to be absorbed in it and what it stands for. What they are doing is, when you think about it, a kind of ritual emulation. They want to do what Leonard Nimoy did: identify with their favorite characters to the point of becoming them. And with these characters, that would seem to include nobility and courage. If Nimoy/Spock was a Christ, then these are his Christians.

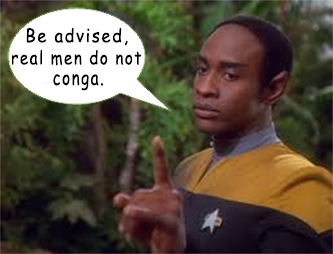

That said, you will never see me dressed up as Harry Mudd or Horatio Jones (the only Trek characters I could possibly pull off) at a fan convention, but you will see me (if you are spying on me) glued to the tube watching Star Trek. Kirk and Spock and Picard make for an edifying spectacle. You watch enough of it and these characters start popping up in your conscience. Once I attended a wedding reception and saw most of the guests flocking to a conga line. Someone beckoned me to join in, but I asked myself, “What would Mr. Tuvok do?†I stayed seated. Okay, maybe that’s a poor example, though I’m sticking with it. I’ve learned much wisdom from the words and examples of other Star Trek characters. You can’t really help it.

That said, you will never see me dressed up as Harry Mudd or Horatio Jones (the only Trek characters I could possibly pull off) at a fan convention, but you will see me (if you are spying on me) glued to the tube watching Star Trek. Kirk and Spock and Picard make for an edifying spectacle. You watch enough of it and these characters start popping up in your conscience. Once I attended a wedding reception and saw most of the guests flocking to a conga line. Someone beckoned me to join in, but I asked myself, “What would Mr. Tuvok do?†I stayed seated. Okay, maybe that’s a poor example, though I’m sticking with it. I’ve learned much wisdom from the words and examples of other Star Trek characters. You can’t really help it.

One final thought. Perhaps mythology, ancient or modern, is made necessary because the “real†world is filled with corrupt, base, and morally mediocre individuals who do not rise above the general morass because they cannot attain escape velocity. If we look to others for clues to how to transcend, to become something better than we are, we most often look in vain. When occasionally we do find a hero, say, like Dr. King, we are willing to look past his sometimes serious flaws because we can see that, to some significant degree, he did manage to launch into the heroic empyrion. Maybe we can emulate him. If we do, we, too, will become myths. Like Leonard Nimoy. Nimoy is gone, but, lucky for us, Spock lives.

So says Zarathustra.

3 Responses to The Second Death of Mr. Spock